Let’s stay with this thought a little longer.

Boromir’s tragedy doesn’t begin with the Ring, and it doesn’t end with his death. It exists in the long, quiet stretch in between — the space where a person becomes so defined by responsibility that they forget how to exist without it.

What we glimpse in the Fellowship is not a man being corrupted, but a man being compressed.

The realization lingering from the earlier reflection is this: Boromir was already living as if failure were not an option, and that belief is far more dangerous than temptation. When failure is forbidden, any solution that promises certainty begins to feel righteous.

Boromir grows up in a culture where strength is not just admired, but required. Gondor does not have the luxury of philosophical distance. Its enemies are visible. Its losses are recent. Its walls bear scars.

And within that context, Boromir is not merely a soldier. He is a symbol.

He is sent to Rivendell not because he is the wisest, but because he is the most convincing proof that Gondor still stands. His presence alone is meant to argue a case: that power, wielded decisively, can still save what remains.

That expectation is never spoken outright, but it shapes everything.

Boromir learns early that his value is measured by outcomes. Victories count. Survival counts. Endurance counts. Inner conflict does not.

There is no ceremony for doubt.

So doubt becomes something private, something slightly shameful. And when doubt cannot be expressed, it does not disappear — it hardens.

This is the psychological cost Tolkien implies but never names: Boromir cannot afford to imagine a future where his strength is insufficient.

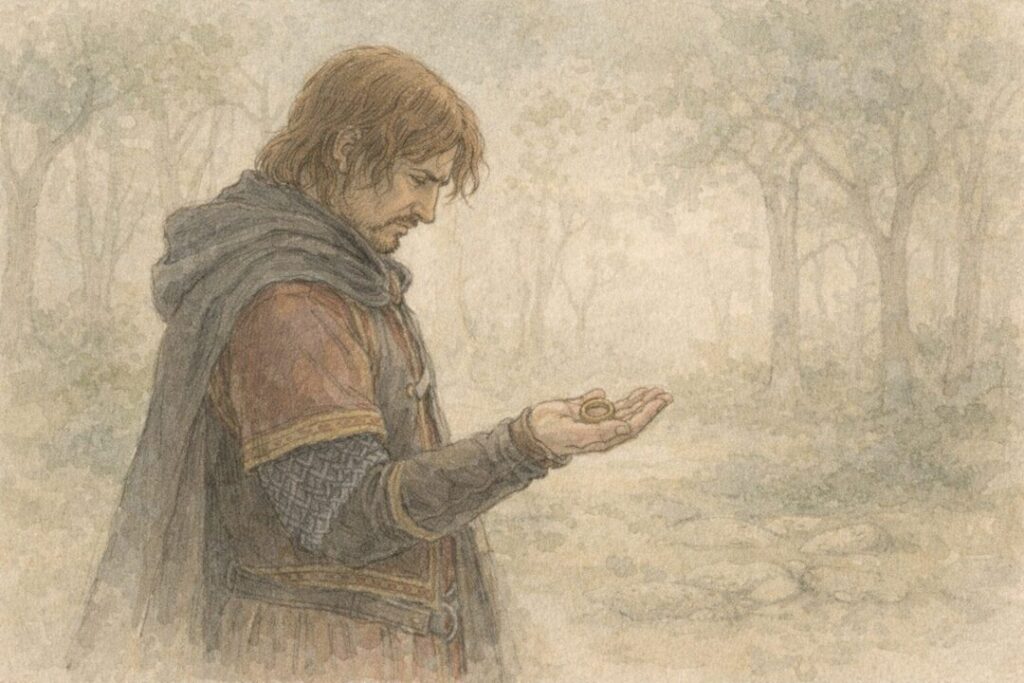

The Ring’s appeal lies precisely there.

It does not promise domination in abstract terms. It promises effectiveness. It promises an end to the unbearable ambiguity of hoping while watching walls crumble.

What makes Boromir’s struggle distinct from others is that he does not want to escape responsibility. He wants to complete it.

That difference matters.

Frodo fears what the Ring might make him. Boromir fears what will happen if he refuses it.

In his mind, restraint looks dangerously close to negligence.

There is another layer that often goes unnoticed: Boromir’s relationship to his father is not just filial, but representational. Denethor does not ask Boromir to succeed; he expects him to embody Gondor’s survival.

That kind of expectation creates a subtle distortion. Love becomes conditional without ever being stated as such. Approval is implied to depend on usefulness.

Boromir internalizes this so deeply that he begins to evaluate himself the same way.

Am I still useful?

Am I still strong enough?

Am I doing enough?

These questions have no resting point.

And when the Fellowship moves slowly, when plans are cautious, when hope is spoken instead of strategy, Boromir feels time slipping away.

The Ring, then, feels less like an object of desire and more like an interruption to despair.

A way to stop asking questions that have no satisfying answers.

One insight rarely explored is how isolated Boromir truly is within the Fellowship. He is surrounded by people who can imagine alternatives to force because they are not watching their homeland bleed in real time.

Aragorn carries legacy, but not command.

Legolas carries distance.

Gimli carries memory.

Boromir carries consequence.

Every delay feels personal.

And that isolation intensifies the internal pressure. Without peers who share his burden, Boromir has no mirror for his fear. Only the Ring seems to understand the urgency he feels.

This is where Tolkien’s restraint as a writer is most effective. He never allows Boromir to articulate this fully. Instead, we see it leak out in tone, in impatience, in insistence.

By the time Boromir reaches for the Ring, the act is not a betrayal born of greed. It is a moment of desperation born of over-identification with duty.

He has mistaken being necessary for being whole.

This is a profoundly human error.

Many people do not collapse under temptation. They collapse under the belief that they are only allowed to exist if they are useful. That rest is indulgence. That uncertainty is weakness. That asking for help is failure.

Boromir’s story resonates because it exposes what happens when responsibility is not shared, but hoarded.

When he finally falls, what follows is not rage or denial, but clarity. Stripped of the impossible burden, Boromir becomes himself again — not as a savior, but as a man.

He fights not to prove worth, but to protect others.

He speaks not in arguments, but in apology.

He dies not grasping for control, but releasing it.

And in that release, something quiet is restored.

Not redemption as spectacle, but dignity.

Boromir’s arc suggests something uncomfortable: that goodness can survive failure, but not perpetual self-erasure. That even the strongest people break when they are not allowed to be incomplete.

The door Tolkien leaves us with is not one of judgment, but of recognition.

We see Boromir not as a warning against ambition, but as a mirror for anyone who has mistaken duty for identity — and wondered, too late, who they might have been if they had been allowed to lay the armor down.

The story does not close with answers.

It closes with the image of a man finally seen, just as he is no longer needed to be more.