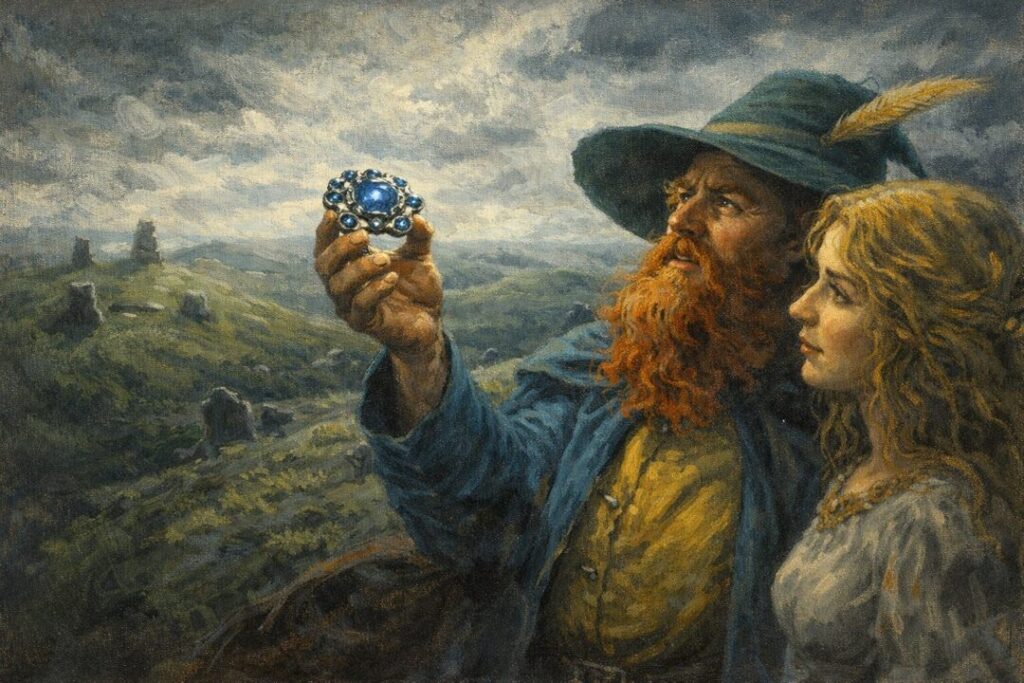

The Fellowship of the Ring gives us only a hint of her: Tom Bombadil rescues the hobbits from a barrow-wight and sorts through the mound’s treasure. Amid the swords and jewels he finds a gem-studded brooch and pauses as if recognizing it. He tells his wife, Goldberry, “Here is a pretty toy for Tom and for his lady! Fair was she who long ago wore this on her shoulder”. That is all we hear about this mysterious woman. No name, no lineage—just a whisper of a “fair lady” and a promise, “we will not forget her.”

The immediate question is clear: Who was this lady? Tolkien’s narrative never answers directly. In fact, the Barrow-wight episode is short on explanation by design – its mood is eerie and mysterious. But we can glean context from other parts of the legendarium. The key is the setting: the Barrow-downs, called Tyrn Gorthad in old tongues. In Appendix A, Tolkien notes that “the mounds of Tyrn Gorthad…are very ancient, and many were built in the days of the old world of the First Age by the forefathers of the Edain”. After the Edain (the ancestors of the Dúnedain) returned from Beleriand, those hills were revered by their descendants, and “many of their lords and Kings were buried” there. In other words, the Barrow-downs contain the tombs of Arnor’s ancient nobility.

It follows that if kings were buried, their queens and princesses likely were too. Indeed, the lore suggests even later, after Arnor split into Arthedain, Cardolan, and Rhudaur, the royal lines of Cardolan ended in tragedy. Tolkien tells us that in TA 1409 Angmar’s Witch-king attacked, King Arveleg I of Arthedain and the last prince of Cardolan were slain. The last prince of Cardolan is traditionally said to have died defending the realm, and some tradition holds that his grave was one of the Barrow-downs. By the end of that war the Dúnedain of Cardolan had fled to Tyrn Gorthad (the Barrow-downs) until a plague ended their line.

Context: Spirits and Tombs

The Barrow-downs’ history helps frame the possible identity of our lady. After Cardolan fell, the Witch-king of Angmar “sent evil spirits…to the Barrow-downs, in order to prevent a resurrection of the destroyed…kingdom of Cardolan”. These spirits animated the bones of the buried, creating the barrow-wights. Some of these fell into the very grave of the last prince of Cardolan, as one account notes that wights “occupied the cairn of the last prince”. In short, after Angmar’s assault the Barrow-downs became haunted – not by the actual ghosts of the dead, but by evil spirits lodged in their tombs.

This is important. The text describes barrow-wights as vile presences, not as sympathetic ghosts of kings or queens. Whether they are fallen Maiar or some dark magic, they do not behave like the people who lie buried; rather, they are malign forces. When Merry awakens in the barrow, he is enthralled by the memories of a warrior prince who fell in battle, but this is framed as the wight’s spell imparting images of history. Tom Bombadil defeats the wight by scattering its treasure to the wind – symbolically breaking the spell of greed and tomb-worship.

All this suggests that if our “fair lady” truly was buried in a Barrow-downs tomb, her own spirit is not wandering free. Instead, the barrow-wights prevent the dead from resting peacefully. If anything remains of her, it is either inert in her tomb or absorbed into the general curse on the Barrow-downs. In short, Tolkien’s story gives us no indication that she became a benign presence.

The Brooch Clue

The one concrete clue is that brooch – pale blue, set with stones “like flax-flowers or the wings of blue butterflies”. Bombadil himself seems to know its significance. His very demeanor changes: he shakes his head as if recalling something, and he says, “Fair was she who long ago wore this on her shoulder. Goldberry shall wear it now, and we will not forget her!”.

This implies a few things. First, the brooch belonged to someone of beauty and status (“fair was she”). The quality of the gem and metal suggest a noble origin, perhaps Númenórean craftsmanship. Second, Tom remembers something about this woman’s life or death, even if he won’t explain it to the hobbits (and by extension the reader). Finally, by giving the brooch to Goldberry, Tom says he will “not forget her,” preserving at least her memory in this symbolic way.

Beyond that, Tolkien’s text is silent. We learn nothing of any names or titles. The hobbits simply accept the brooch and the moment passes. In fact, for all we know, Tom was simply engaging in an old custom of honoring the dead: Goldberry becomes the bearer of the lost lady’s token. The narrative neither confirms nor denies whether Tom truly knows her story or is speaking in general reverence for all that was lost.

Identity and Speculation

Because Tolkien leaves us no details, fans have long speculated about who this “fair lady” might be. All such ideas are conjecture, since there is no canon source giving an answer. For example, one common interpretation is that she could have been a queen or princess of Arnor’s northern realm (Cardolan). Cardolan’s royal line ended in the Early Third Age, and a queen who died in battle or flight could plausibly have been entombed on the Downs. Perhaps she was the wife of the last prince of Cardolan, slain in TA 1409 – or even an earlier royal who fell in one of the wars with Angmar. But again, Tolkien does not say so.

Another suggestion is that she might have been a noblewoman of the Edain – the first Men of the north – from ages long past, whose descendants revered her memory. The brooch’s style (blue stones, many-shaded) has led some readers to guess she might have been an Elf or Maia in disguise, but that clashes with the context: the Barrow-downs were for Men, not Elves, and no elf queen is known to have lived there. Tolkien never explicitly ties any Elven figure to the Barrows.

A more cautious way to put it is this: If we assume she was a person who lived and died in those hills, then the natural candidates are women of Arnorian nobility. The vast time-depth of Tolkien’s world means she could have lived in the First Age, Second Age, or even early Third Age – any time the northern men had kingdoms. But without textual evidence, such theories remain imaginative interpretation.

We must also consider Tolkien’s style: he often leaves minor mysteries unexplained, to evoke a sense of depth. The identity of the brooch-wearer may be one such narrative thread meant to be gently tugged at by readers’ imaginations, rather than firmly answered. Indeed, as one Tolkien scholar notes, Bombadil himself seems to treat this discovery with a touch of nostalgia or sadness – an acknowledgement of the rich history buried here, even as the present story moves on.

What Became of Her?

What, then, became of this queen or noblewoman? Canonically, we can only say she remains one of the many unnamed dead beneath the grass. If she existed as a real historical figure, she was buried in her barrow along with the others, and her mortal life ended just like any other.

The narrative gives no indication that her soul lingered to become one of the wights. Remember: Barrow-wights are not simply the ghosts of those interred, but malevolent spirits summoned by dark magic. When Merry wakes from the wight’s enchantment, he describes only a battle and a stabbing spear, with no mention of a queen crying out. Bombadil’s exorcism banishes the wight’s spirit, but there is no suggestion of freeing the spirit of a queen or any other person inside – simply the destruction of the evil.

It is possible, in an untestable speculation, that Bombadil’s promise “we will not forget her” means he is laying her spirit to rest in a small way. By honoring her memory through Goldberry, he ensures that at least one gentle corner of Middle-earth remembers the beauty that once existed. But Tolkien never makes this explicit. The practical effect is that her story is left to the reader to imagine.

In terms of Middle-earth’s world, though, no miraculous outcome is recorded. It’s not like Frodo and Sam who bear ring-scars and find healing in the West; this unnamed queen is not granted a grand redemption or an escape. If anything, her fate is emblematic of the many lesser-known tragedies Tolkien alludes to.

A Fragment of History

The haunting “queen of the Barrow-downs” is not central to the Ring-quest plot, but her shadow in the text reminds us that Middle-earth is a layered world. Many battles were fought long before Bilbo’s time. Many nobles died and were forgotten as ages passed.

Tolkien himself hinted at this when he described the Barrow-downs: “Gold was piled on the biers of dead kings and queens; and mounds covered them” (an evocative narrative passage in Fog on the Barrow-downs). He was consciously linking this hobbit episode to a history that dwarfs the Fellowship’s adventure. In that sense, the lady of the brooch is real – not as a character in the story, but as a symbol of all the unheard stories lying beneath those ancient hills.

Bombadil’s brief reverie over the brooch is essentially Tolkien winking at us: there are untold lives behind every tomb. We see just a token – Goldberry’s new brooch – but not the person. The lady’s actual tale is “gone beyond the circles of the world,” to borrow a phrase Tolkien used elsewhere.

The Answer and Its Meaning

So, who was the Barrow-wight “queen”? In strict terms, Tolkien never tells us. We have only implications:

- The Barrow-downs were the sacred burial sites of Arnor’s old kings.

- One of those kings was the last prince of Cardolan, whose tomb may have housed wights.

- Tom Bombadil found a royal jewel there and honored a nameless lady.

Put it together and you can imagine a story: perhaps a noble lady (a queen or princess) of old Arnor died defending her land, and her tomb once gleamed with treasure. Centuries later the Witch-king desecrated that tomb with a wight, and Bombadil has now unwittingly rescued a keepsake from it. But all of this is inference.

Importantly, if you decide she was a real person, the text gives no evidence of her surviving on after death. She is not shown guiding the wight or interacting with our heroes; she is simply remembered in Tom’s gentle words. The story is about the fallen world, not about her specifically.

In the end, the Barrow-downs queen remains a mystery of the lore. Tolkien chose to leave her unnamed, as he left many details unspoken. This allows readers to wonder and fill in gaps, but it also reflects his theme that history is vast: for every character we meet, countless others fade into silence.

Why This Mystery Matters

You might ask: why focus on a figure who never appears? In Middle-earth, even minor hints serve a purpose. The mention of the queen does three things:

- Age and depth: It reminds us how long these hills have witnessed history. The hobbits’ adventure is just one moment in that long timeline.

- World-building: It shows that Tom Bombadil has a memory stretching far beyond the Shire. He speaks as though he knew her, which makes Middle-earth feel lived-in.

- Theme of mercy: Just as Bilbo’s mercy to Gollum echoes in Frodo’s fate, here Tom’s quiet kindness to a dead queen’s memory echoes the work’s gentle moral: even in victory, we honor the humble and forgotten. He says “we will not forget her,” and indeed neither shall we now, for we are still asking the question centuries later.

The question who was she changes the scene subtly: it turns a narrow escape story into a glimpse of a wider tragedy. It shows that the fall of Arnor was not just about kings, but families and people (including unnamed queens) who suffered.

But Tolkien intentionally leaves the loop open. That single line “Fair was she…” rings like an unanswered question into the silence. It invites us to imagine, but it never lets us conclude. Maybe that’s the point: not every secret is revealed, even to those we call heroes.

The Barrow-wight Queen may not have a name in the text, but through Tolkien’s hints she continues to haunt the imagination. After all, sometimes “the greatest acts are not the loudest – but the longest”, and sometimes the deepest mysteries lie in the quietest corners of the story.

In the Barrow-downs, the queen lies silent under earth and stone, her story half-told by a wandering minstrel of the woods. All we can do is remember that in Tolkien’s world, even the smallest gesture of remembrance – like a brooch placed on a shoulder – can bridge the gap between legend and our own curious hearts.