There is a moment at the West-gate of Moria that feels like a story trying not to look at itself.

The Company has failed on Caradhras. They have turned back. They are tired, cold, and running out of choices.

Then they reach the old road—once an artery of friendship between Elves and Dwarves—and discover that the road no longer ends in stone.

It ends in water.

The lake that shouldn’t be there

The approach to the West-gate is described with a specific wrongness: the gate-stream has been dammed, and a dark, still lake now fills what used to be a shallow valley. The surface does not mirror the sky. It lies there like something shut and holding its breath.

Even before the Watcher appears, the landscape itself has become an obstacle—and a warning. It is not simply that the path is blocked. It is that the water looks “unwholesome,” as if the place is telling them to turn back.

This matters for the “Sauron created it” question because the Watcher is not introduced as a lone monster in a natural pool. It is introduced as part of a deliberate-feeling sequence: a dammed stream, a drowned valley, a hidden door, and a lake that behaves like a threshold.

But the text does not say who dammed the stream. It does not attribute the change to Orcs, to the Watcher, or to any servant of the Enemy. It simply states the fact: the Sirannon “had been dammed.”

The holly trees and the memory of friendship

At the end of the drowned road stand two great holly trees, stiff and silent, “standing like sentinel pillars.” Gandalf explicitly explains what they mean: holly was the token of Hollin, planted to mark the end of its domain, because the West-door was made chiefly for Elvish use in their traffic with the Lords of Moria.

This is not incidental lore. It frames the West-gate as a place where history is layered into the landscape: friendship → closure → abandonment → a strange new peril.

The Watcher arrives, then, not merely as a fight scene, but as a violation of what this threshold used to represent.

What the Watcher does—and what we are not allowed to see

When the Watcher finally attacks, the description is vivid but incomplete.

The text gives us the tentacles: pale-green, luminous, fingered. It gives us their number—more than twenty. It gives us the stench, the boiling of the lake, the sudden escalation from one grasp to many.

But it withholds the body.

We never get an outline. We never get eyes, teeth, or shape. We get only the parts that reach out of the water, and the implied unity behind them: many arms, one purpose.

That withholding is the first reason the “Sauron created it” theory struggles: the text refuses to place the Watcher in any known category. It is not named like a Troll. It is not described like a warg. It is not explained as a spawned monster of war.

It is simply there—and then, suddenly, it is touching you.

Gandalf’s one clue: “crept, or has been driven out”

After the escape, Frodo asks the obvious question. Gandalf answers with the most unsettling kind of lore: an admission of ignorance.

He does not know what it was.

All he offers is a guess about motion and origin: that something has “crept, or has been driven out of dark waters under the mountains.” And he adds that there are “older and fouler things than Orcs” in the world’s deep places.

This is the nearest the text comes to an origin story.

And it is not the language of a planned ambush.

It is the language of a world that contains things even the Wise have not catalogued.

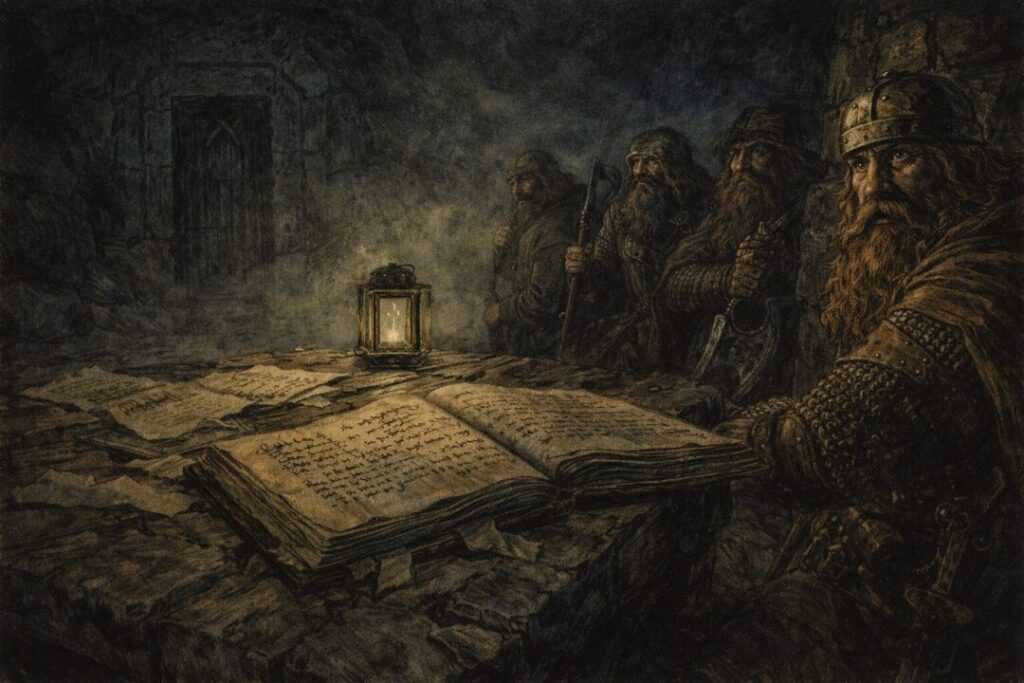

The Mazarbul record changes the timeline

If the West-gate scene stood alone, a reader could still try to argue: perhaps this creature was placed here because the Company was coming.

But the narrative does not leave it alone.

Inside Moria, the Book of Mazarbul records the doom of Balin’s attempt to reclaim the realm. In its final lines, the Watcher is named as an instrument of entrapment: the pool rises “up to the wall at Westgate,” and the Watcher takes Óin.

Gimli’s response makes it practical, not poetic: it was well for the Fellowship that the pool had sunk a little, and that the Watcher was sleeping “down at the southern end.”

This does not tell us what the Watcher is—but it tells us what it is not.

It is not a creature invented for one night.

It was there before, and it remained.

So could Sauron have “created” it anyway?

Here we have to stop and define terms the way the texts define them.

In Middle-earth, “making” living beings is not the same as building towers or forging rings. The Silmarillion makes that boundary explicit when Ilúvatar confronts Aulë for attempting a thing beyond his authority. Aulë can shape bodies, but he cannot freely originate independent life; Ilúvatar must accept the work and grant it a place.

The same worldview is applied to the Enemy. In the Silmarillion’s discussion of Orcs, it states that they multiply like the Children of Ilúvatar, and adds that Melkor could not make anything with life of its own, “so say the wise.”

And within The Lord of the Rings, Frodo articulates the same principle in plain speech: the Shadow can mock and ruin, but cannot make “real new things of its own.”

So if “created by Sauron” means a new living kind brought into being from nothing, the texts push against that idea as a rule of the world.

If “created” is meant more loosely—bred, twisted, trained, stationed—then we return to the question of evidence.

And the evidence remains thin.

Gandalf does not identify the Watcher as a servant. He does not even claim it is known to the Enemy. He only suggests it rose—or was driven—out of waters beneath the mountains.

The deeper hint: not all evils answer to the Dark Lord

There is one more passage that matters—not for proof, but for tone.

Later, recounting his pursuit of the Balrog far beneath Moria, Gandalf says that “nameless things” gnaw the world far below the Dwarves’ delvings, and adds: “Even Sauron knows them not.”

This line is often brought into Watcher discussions, because it offers a category for horrors that exist outside the Dark Lord’s command.

But the canon never equates the Watcher with these nameless things.

So the most responsible phrasing is: the text establishes that there are deep entities unknown even to Sauron, and it establishes that the Watcher seems to have come out of dark waters under the mountains—but it never states that these are the same.

A conservative conclusion

If you follow the texts strictly—no invented backstories, no unseen motives, no fan-made biology—then the answer is not dramatic.

The Watcher’s origin is not given.

What is given is this:

It lives in the dammed waters before the West-gate.

It attacks with many tentacles but one guiding will.

Gandalf does not know what it is, only that it seems to have come (or been driven) from dark waters under the mountains.

It was present in the time of Balin’s colony, taking Óin and helping to make escape impossible.

And the legendarium’s broader metaphysics warns us against attributing true “creation” of living beings to any dark power as if it were unfettered manufacture.

So: was it a monster made by Sauron?

Canon cannot support that claim.

What canon can support is something more unsettling: that at the borders of Moria there are dangers that do not arrive with banners and names. Some things are simply there—older than the stories we know, and perhaps not fully understood even by the Wise.

And that, in its own quiet way, may be the point.