It’s one of the oldest questions readers carry out of the Shire.

Not because the Shire feels incomplete—quite the opposite. Hobbit-life is drawn so completely that it seems like it must have roots we can trace: older families, older customs, older stories buried under the green hills.

And yet, when we ask the simplest version of the question—where did Hobbits come from?—the legendarium answers with a paradox:

Hobbits are described as “very ancient”… and at the same time they seem to “appear” in written history late, abruptly, and almost by accident.

The solution to that paradox is not a hidden genealogy or a lost creation-myth.

It’s something quieter: a trail of canon clues that tells us what can be known, what cannot, and why the Hobbits’ “origin” is fundamentally different from the origin stories of more famous peoples.

They are kin to Men, but the exact line is lost

The Prologue begins by closing one door firmly. Hobbits are “relatives” of Men—closer to Men than to Elves or Dwarves—and they once spoke the languages of Men “after their own fashion.”

But then it immediately limits how far that statement can be pushed: “what exactly our relationship is can no longer be discovered.”

That is not evasive wording. It is the text telling you, directly, that the sort of ancestry-chart many readers want is unavailable inside the surviving records.

A separate authorial note preserved in the letter to Milton Waldman says the same thing even more directly: Hobbits are “meant to be a branch of the specifically human race (not Elves or Dwarves),” with no “non-human powers.”

So the “true origin” begins with a constraint:

Hobbits are human-kind.

But the details of how that branch separated, and how long ago it happened, are not preserved as recoverable history.

The Prologue places their earliest remembered homeland by the Great River

If the bloodline is lost, what remains is geography—because geography is the one thing even a wandering people can half-remember.

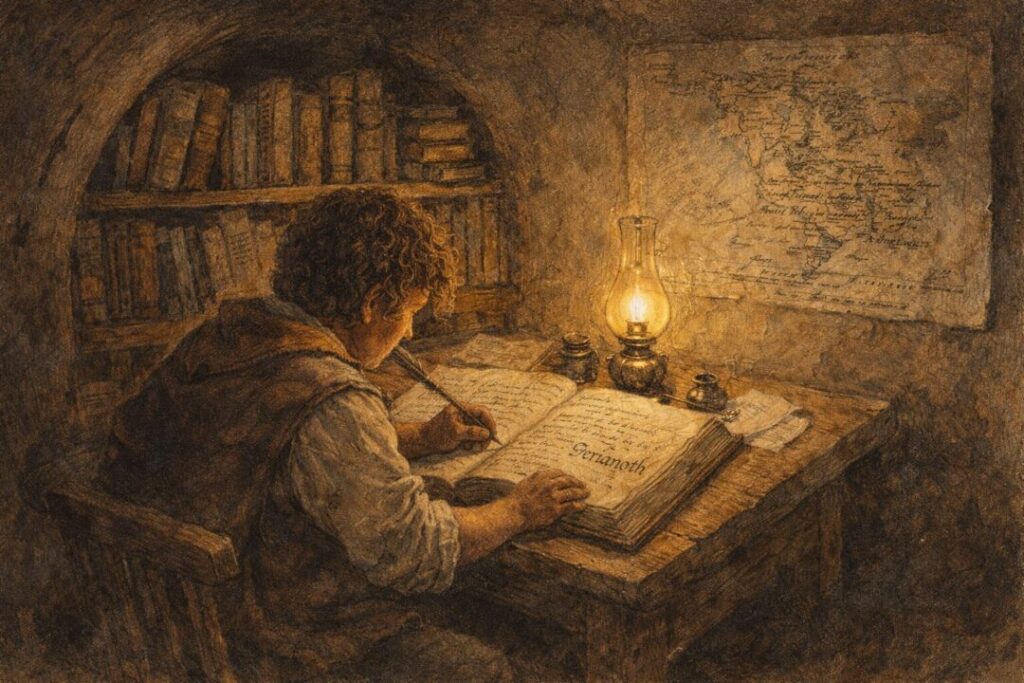

The Prologue says that in Bilbo’s time Hobbits preserved no knowledge of their “original home.” Their own written records begin only after the settlement of the Shire, and their most ancient legends barely look further back than their “Wandering Days.”

Even so, it adds that the earliest Hobbit tales “seem to glimpse” a period when they dwelt in the upper vales of Anduin, “between the eaves of Greenwood the Great and the Misty Mountains.”

That line does two important things at once:

It gives us a location anchored in the wider map of the North—river-vales, forest-edge, mountain-foot.

And it frames the memory as partial: a “glimpse,” not a chronicle; a remembered region, not a dated event.

So canon does not say “Hobbits originated in X year in X place.”

It says that the earliest stories they still possessed in later times point back to that river-land as an old dwelling.

Why did they leave? The texts give reasons, but no certainty

When Hobbits cross the mountains and enter Eriador, they step into the part of the world where the reader meets them: the North-west, roads and ruins, old kingdoms fading.

But the Prologue is careful with causation. It says that why they undertook “the hard and perilous crossing” into Eriador is “no longer certain.”

Even then, it reports what Hobbit accounts say: Men were multiplying, and a shadow fell on Greenwood until it became darkened and gained the name Mirkwood.

Notice the shape of the explanation.

It does not describe a single catastrophe that drove them out. It gives pressures—crowding, fear, the sense of a changing world—and it places those pressures in the same broad span in which the wider histories note a “shadow” on Greenwood.

So the canon stance is conservative:

The motive is remembered in outline, not in detail.

The crossing is real, but the precise trigger is not recoverable.

That restraint is part of the answer. The Hobbits’ origin story is meant to feel like a folk-memory at the edge of history.

Their first appearance in written history is later—and very specific

Here is where readers often get confused, because the Prologue calls Hobbits ancient, and yet the written annals don’t mention them early.

Appendix B resolves the timeline without resolving the deeper mystery.

In Third Age 1050, the Tale of Years records: “The Periannath are first mentioned in records, with the coming of the Harfoots to Eriador.”

This is not the text saying, “This is when Hobbits came into existence.”

It is saying: This is when scribes begin writing them down.

That difference matters.

The Prologue explicitly says Hobbits had lived quietly in Middle-earth for “many long years” before other folk were even aware of them. In other words, their absence from early records is not proof of non-existence; it is a feature of how they lived, and of what other peoples chose to record.

So “true origin” in canon splits into two tracks:

An untraceable beginning “far back in the Elder Days.”

A traceable appearance in annals in 1050, linked to westward migration.

The three Hobbit-kinds are a key clue, not just trivia

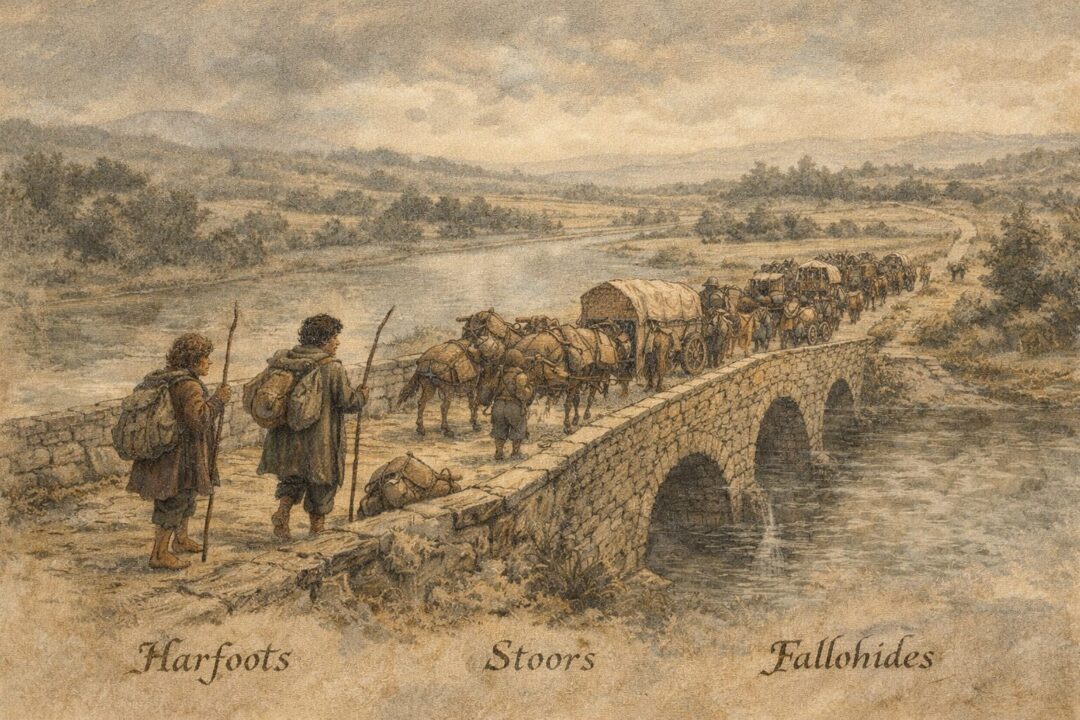

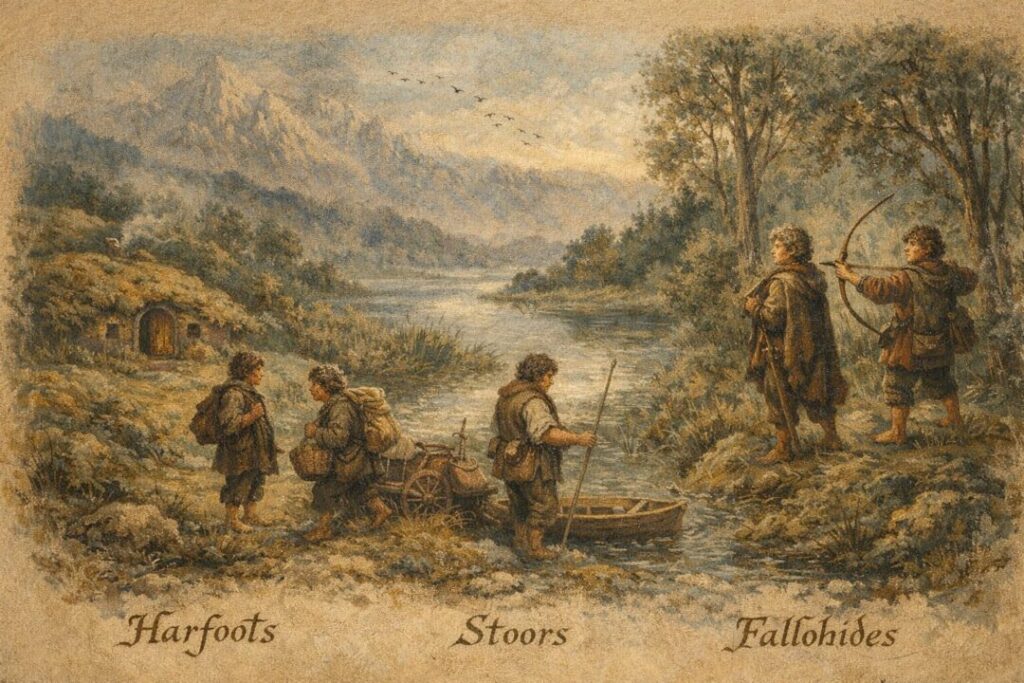

The Prologue adds a detail that many adaptations flatten, but which matters for origins: before the crossing of the mountains, Hobbits had already become divided into three distinct kinds—Harfoots, Stoors, and Fallohides.

This is not simply a description of looks. It is evidence of long habitation and adaptation across different environments.

Harfoots are described as browner of skin, smaller, beardless and bootless; they prefer highlands and hillsides, had dealings with Dwarves, and long lived in mountain foothills. They wandered west early, and preserved most strongly the ancestral habit of tunnel- and hole-dwelling.

Stoors are broader and heavier in build, preferring flat lands and river-sides; they lingered long by the banks of the Great River, were less shy of Men, and their later wanderings took them into other lowland regions before some returned northwards.

Fallohides are fairer of skin and hair, taller and slimmer, lovers of trees and woodlands; in temperament they are described as friendlier with Elves and often found as leaders among the other kinds; their “strain” is noted among prominent families in later times.

For an “origins” question, the point is not which kind is “most Hobbit-like.”

The point is that the three kinds already exist before the migration into Eriador—so the people must have been living long enough, in varied enough lands, for those differences to become established.

That is one of the strongest canon arguments for Hobbit antiquity, even while their beginning remains historically unrecoverable.

From wandering folk to settled communities

The Prologue continues the trail past the crossing and into the part of the story-world that becomes familiar.

In Eriador, Hobbits encounter both Men and Elves, and there is “room to spare” in a North-kingdom already falling into waste. Hobbits begin to settle in ordered communities.

Most of those early settlements vanish long before Bilbo’s era, but one endures: Bree and the surrounding woods.

The Prologue adds that in those early days Hobbits likely learned letters and writing after the manner of the Dúnedain, who had learned the art from Elves; and they forgot whatever languages they had used before and thereafter spoke the Common Speech (Westron).

Appendix F complements this by stating there is no record of any language peculiar to Hobbits and that they seem always to have used Mannish languages near whom (or among whom) they lived; it also treats their adoption of the Common Speech as a quick transition once in Eriador.

So canon gives a picture of origins that is cultural as much as biological:

They are human-kind.

They lived long in river-land and wild margins.

They migrated west, became visible to record-keepers, and adopted the speech and crafts of their neighbours.

The Shire is the outcome of that history, not the start of it

Finally, the great settling.

Appendix B records that in 1601 many Periannath migrate from Bree and are granted land beyond the Baranduin by King Argeleb II.

The Prologue adds narrative colour: in 1601 the Fallohide brothers Marcho and Blanco set out from Bree, obtain permission from the high king at Fornost, and cross the brown river Baranduin with a great following of Hobbits—a transition from “legend” into a dated reckoning of years.

By the time we meet Bilbo Baggins and later Frodo Baggins, that long movement has been forgotten into comfort; the Shire feels like “home” because it is the end-point where wandering finally becomes memory.

So what are the “true origins”?

If “origin” means “creation,” canon does not give a creation-myth for Hobbits the way it gives one for Dwarves, and it explicitly says the beginning lies in times now lost.

If “origin” means “what are they,” the answer is firm: they are a branch of Men.

If “origin” means “where did they come from before the Shire,” the trail is clear enough to trace:

Their earliest remembered dwelling is by the upper Anduin, between Greenwood and the Misty Mountains.

They migrate west into Eriador, and in 1050 they become visible to written records with the coming of the Harfoots.

They settle, learn, blend with wider cultures, and in 1601 are granted land beyond the Baranduin that becomes the Shire.

And if “origin” means “why is it so hard to pin down,” the Prologue answers that too:

Because Hobbits kept few records early; because larger peoples did not consider them important enough to track; and because their story is, in a real sense, the story of a people who survived by remaining beneath notice until the day they could no longer do so.