At first glance, the answer feels obvious.

Yes.

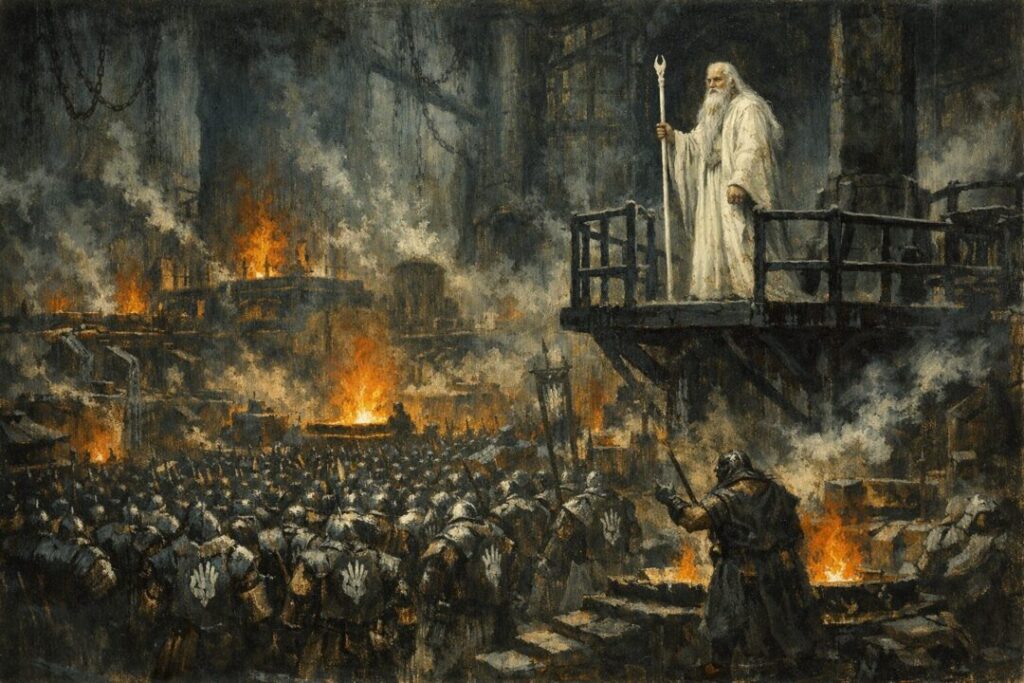

By the time open war begins, Saruman already commands thousands. The forces that march to Helm’s Deep include Uruk-hai, Dunlendings, and other Orcs. The Deeping Wall is destroyed. The Hornburg nearly falls.

Rohan survives—but not comfortably.

So it is natural to ask: if Saruman had more time, could he have expanded the Uruk-hai into something unstoppable?

The texts allow us to approach this carefully.

But they also impose limits.

What the Texts Actually Say About the Uruk-hai

The word “Uruk” itself is not unique to Saruman. In The Lord of the Rings, “Uruks” are described as large, soldier-Orcs used by Sauron as well. The Black Uruks of Mordor appear before Saruman’s open rebellion.

However, Saruman’s Uruk-hai are presented as distinctive.

In The Two Towers, Aragorn observes that the Orcs who captured Merry and Pippin are “large, swart, slant-eyed,” and bear the White Hand of Isengard. They march by day. Uglúk, their captain, shows discipline and authority uncommon among Orc companies seen elsewhere.

Treebeard gives the most pointed observation. He remarks that Saruman has “taken up with foul folk” and has “made some of his own.” He notes that these Orcs can endure sunlight better than others.

The implication—carefully phrased in the text—is that Saruman altered or bred Orcs to improve their battlefield utility.

The films suggest crossbreeding with Men explicitly. The books are more restrained. They do not provide a technical explanation. They show results.

Stronger.

More disciplined.

More adaptable.

But never infinite.

How Large Was Saruman’s Army?

At Helm’s Deep, the Rohirrim estimate that around ten thousand enemies approach. This force includes Uruk-hai, Orcs, and Men from Dunland.

Ten thousand is not trivial.

For comparison, Gondor later struggles to muster comparable strength quickly when Minas Tirith is threatened.

Saruman had achieved this in secrecy.

He fortified Isengard.

He cut down the trees of Nan Curunír.

He organized industry.

He centralized command.

Given more time, could he have doubled that number?

Possibly.

Nothing in the texts states that Saruman had reached an absolute numerical ceiling by the time of Helm’s Deep. His breeding pits were active. His alliance with Dunland was functional. He was still preparing operations against Rohan even before Sauron’s full assault on Gondor.

But numbers are only one axis of power.

And this is where speculation must slow.

The Limit of Saruman’s Authority

Saruman is powerful—but he is not Sauron.

This matters.

Sauron is described as having dominated the will of Orcs for ages. His power over them is spiritual as much as political. When the Ring is destroyed, his forces collapse into confusion and flee.

Saruman does not possess that same metaphysical dominance.

His control appears administrative and charismatic rather than absolute. His voice is persuasive—dangerously so—but it does not bind wills in the same manner as the One Ring binds.

When Isengard falls and the Ents flood the pits, Saruman’s army does not rally for a last coordinated stand. At Helm’s Deep, once Gandalf arrives with Erkenbrand’s reinforcements and the Huorns encircle the survivors, the Uruk-hai break.

They fight fiercely—but they do break.

This suggests something important: Saruman improved the tools of war. He did not fundamentally alter their nature.

Orcs in Middle-earth are not portrayed as endlessly self-sustaining strategists. They quarrel. They fear stronger masters. Their loyalty is often coercive.

Nothing in the texts suggests Saruman had solved that structural instability.

The Problem of Resources

There is also a practical constraint.

Isengard is not Mordor.

Mordor is vast, fortified by mountains, fed by long-established networks of slaves and industry. Barad-dûr towers over a land shaped for war.

Isengard, by contrast, is a single stronghold within a ring of stone. Saruman expands industry aggressively, but Treebeard’s testimony makes clear that this expansion is recent and destructive.

The forests fall quickly.

Fuel burns quickly.

Production requires time and materials.

Even if Saruman could breed more Uruk-hai, sustaining and equipping a massively expanded army would require supply chains that the text never shows him fully establishing beyond regional reach.

His campaign is focused on Rohan.

There is no indication he had secured maritime access, large-scale agricultural redirection, or distant tributary regions comparable to Mordor’s reach.

So while expansion is plausible in theory, exponential growth is not textually supported.

Would Time Have Changed the Outcome?

Here the speculation becomes sharper.

If Saruman had waited—if he had not attacked Rohan prematurely—he might have coordinated more closely with Sauron. The appendices show that Sauron valued him as an ally, at least initially.

But this introduces another limit.

Saruman’s ambition is independent.

He seeks the Ring for himself.

His long-term goal is not subordination to Mordor, but replacement.

That creates tension.

An unstoppable Uruk-hai empire would inevitably collide with Sauron’s dominance. And Sauron’s power—rooted in the Ring—would eclipse Saruman’s improvements in breeding or tactics.

In other words, even if Saruman had doubled or tripled his forces, he would still face a superior dark power unless he secured the Ring.

And without the Ring, the texts consistently show that Saruman’s influence diminishes.

When Gandalf confronts him at Orthanc after Isengard’s fall, Saruman’s voice still carries weight—but not command.

When he reaches the Shire, his power is petty and local. He commands ruffians, not legions.

His arc suggests decline once military dominance is lost.

The Deeper Constraint

There is one final limit, implied rather than stated.

Middle-earth resists consolidation under lesser tyrants.

The Ents rise unexpectedly.

Rohan endures.

Gondor holds.

The Rohirrim answer the Red Arrow.

The Dead of Dunharrow fulfill their oath.

The West unites at the Black Gate.

Again and again, Saruman’s calculations fail not because his soldiers are weak—but because he misunderstands the resilience of free peoples.

An unstoppable force in Middle-earth requires more than numbers.

It requires spiritual domination.

And that belongs, within the narrative, uniquely to Sauron through the Ring.

Saruman imitates.

He industrializes.

He breeds.

He organizes.

But he does not create a new metaphysical order.

So Could He Have Succeeded?

He could have grown stronger.

He could have fielded more Uruk-hai.

He could have devastated Rohan more completely if events had shifted slightly.

But the texts give no indication that he was on the path to unstoppable supremacy.

His power is impressive—but bounded.

Bounded by resources.

Bounded by divided ambition.

Bounded by the limits of imitation.

And ultimately, bounded by a world that does not yield permanently to second-tier tyrants.

Saruman’s tragedy is not that he lacked potential.

It is that he mistook improvement for mastery.

And in Middle-earth, those are not the same thing.